What Does It Take to Build a Multilingual Web

IndieWeb Carnival: Multilingualism in a global Web

This post is also available in Spanish.

I grew up in the US and have the privilege of knowing English. When I travel internationally, I usually can communicate with an employee in my native language. This privilege extends to the web as well. It is rare for me to encounter a site that is not available in my native language.

Why shouldn’t the web be English-only?

I don’t think most people explicitly expect the web to be English-only. But it think it’s worth asking the question because can be an implicit expectation. On the one hand, a common language is handy for a community. It makes it a lot easier to find common ground. But as someone trying to learn Spanish and has traveled to places that only communicated in Spanish, I’ve had a taste of the challenges of not being a native speaker.

Language barriers hold back information. They also are intimidating. Have you ever tried to order a meal or drink where you can’t hear the employee due to noise, a bad intercom, or a thick accent? It’s uncomfortable to only understand a portion of what was said! So I’m concerned that the web might only be welcoming to English speakers when most pages are only in English.

This isn’t true everywhere. Thanks to the hard work of writers, translators, and technologists, some parts of the internet hold a wealth of information in other languages. When researching historical sites in Mexico, I’ve found the Spanish language versions of many Wikipedia pages are much more complete than the English versions.

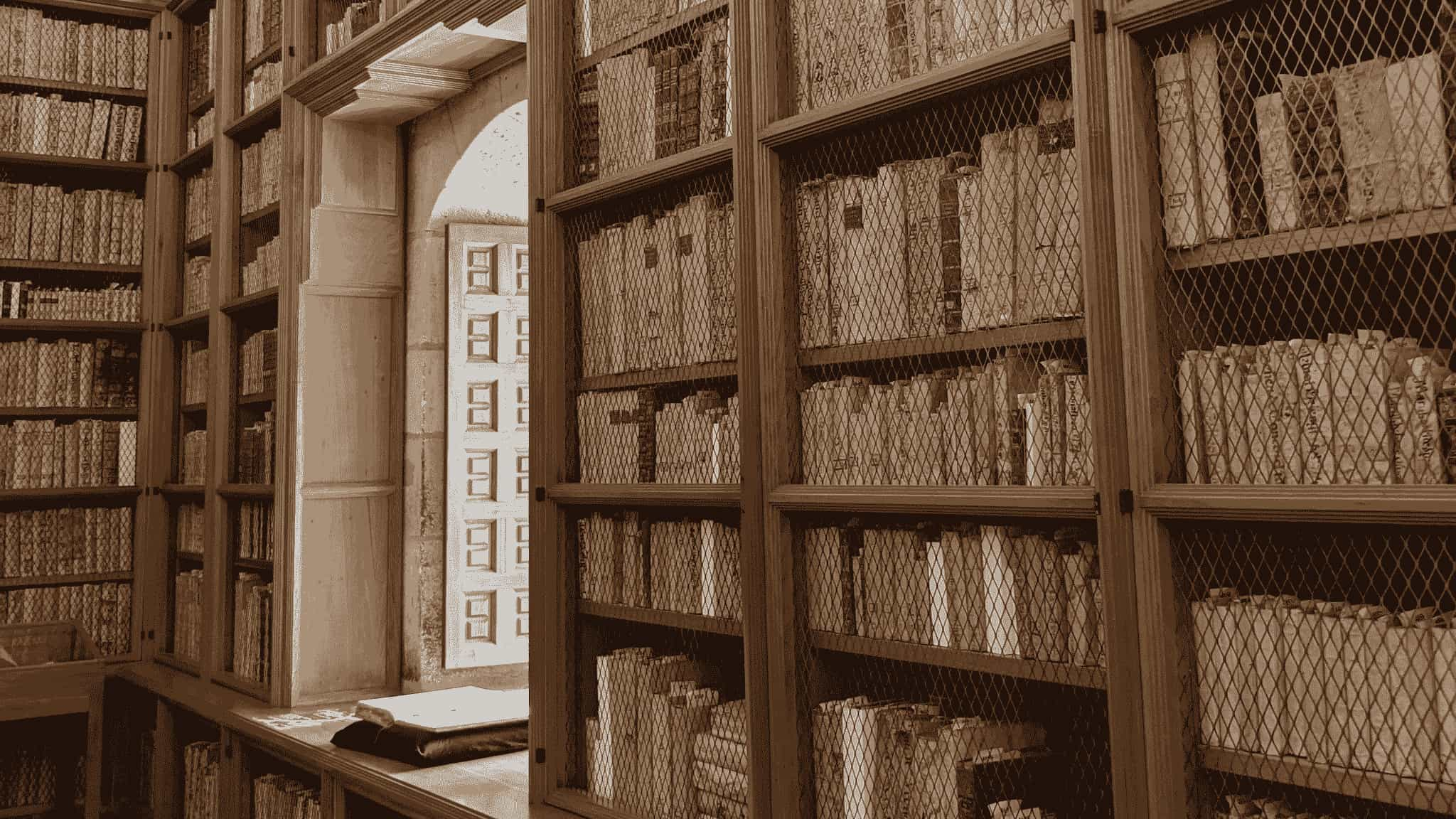

It’s also worth recognizing that smaller, local languages face an even larger risk. When we walked through la Biblioteca de Investigación Juan de Córdova in Oaxaca, they talked about their work preserving the pre-Spanish culture in southern Mexico and offering services in native languages. While I don’t have anything to contribute there, I think it’s important to push for a multilingual web that doesn’t just include the biggest languages, but also keeps at-risk languages alive.

Personal sites are an interesting opportunity for improvement. Individuals don’t have to get approval to spend time translating their pages. People can choose to add languages they are familiar with. That was one thing I noticed and loved about this month’s IndieWeb carnival entries. But personal sites are a volunteer effort, unpaid labor with often no monetary incentive to translate.

Making my own contributions

I’ve been wanting to add Spanish translations to my website for a very long time, at least since January 2020. For years that was too daunting of a task. But when this month’s IndieWeb Carnival topic came up, I decided I needed to put in the effort.

So I started working on adding translations. There are a lot of technical pieces I may one day get into, but the short version of the story is, that it wasn’t plug-and-play. But when I finally got around to the actual translation piece, I found it was a good exercise. I learned a lot about how websites identify the language they are written in so tools like browsers and search engines can help people find content in their language. I also learned how to build a site that supports translation beyond just the main content; making sure navigation text, SEO tags, and labels only seen by accessibility tools are also translated.

Site translation as a language learning tool

I’m still working to improve my Spanish language skills. I have had my phone in Spanish for a few years now. While traveling Latin America in 2019 I took private lessons with some local tutors. When we visited Mexico with friends this summer, I intentionally chose to use Spanish where I could even though my friends spoke better English than I could Spanish. I complete lessons with Duolingo daily. However, each of those types of learning was focused on specific use cases. So while I’m comfortable ordering in Spanish at a restaurant, speaking Spanish with my neighbors is still intimidating as I fumble over words for things around the house or our upcoming plans. I’m less comfortable using technical jargon in Spanish which is unfortunate for someone who works on computers for their day job.

But the act of translating is great practice. Compared to practice phrases, translating my own words helps build the vocabulary I’d actually use. I do rely heavily on tools like Google Translate, but I review every word and frequently reword text that doesn’t sound like my voice.

The work never stops

Now that I am set up to post Spanish on my site, I’m looking forward to adding more content. Some pages like my travel photo posts should be easy to translate. I know that I’ll never get 100% of my content translated, but I’m excited to make more contributions.

I’m also hoping to improve the IndieWeb wiki’s Spanish language content. At the time of writing, there are only 2 pages in Spanish. Helping make IndieWeb content more accessible to Spanish-language communities could help encourage more people to write their own Spanish-language content.

Thanks to ZinRicky for the push I needed to start contributing to the multilingual web!

I know the quality of my translations could be improved and there are likely issues with how everything is linked together. So if you notice problems or have suggestions on my Spanish translations, please contact me via email. But I didn’t want fear of messing up to hold me back from finally making a contribution to building a multilingual web.

This post is a submission to IndieWeb Carnival October 2024 - multilingualism in a global Web, hosted by ZinRicky for the IndieWeb Carnival.

Responses

See how to respond...

Respond via email

If you'd prefer to message me directly, send an email. If you'd also like your message to be visible on the site I can add it as a comment.

Reply via Email

Respond from another site

Responses are collected from posts on other sites. Have you posted somewhere that links to this page? If so, share the link!